May 2020

Before we lived through it, I could not have imagined our nation would be in a state of semi-quarantine due to a global pandemic. Nevermind that the public reaction to the killing of George Floyd, a black man from Houston, by a Minneapolis police officer would become such a watershed moment in the worldwide Black Lives Matter movement.

In the weeks after his death, Confederate monuments were removed from public spaces, the effort to rename military bases named for Confederate officers gained momentum, and Juneteenth, a traditional Texas celebration of the belated end of slavery here, was recognized in communities all around the country.

It was in this climate that I decided to return to the document I found the year before.

1865-1874

In the post-Civil War period in Texas, the Powers That Were began enacting untenable laws limiting the rights of the formerly enslaved. When federal Reconstruction got under way, Texas government officials were removed from office. Several tumultuous years followed, marked by political unrest, violence, and a destabilized economy.[1] Those were among the repercussions of freeing what one newspaper report claimed was $85 million worth of slaves.[2]

I don’t have any idea how close that is to a “real” number. But to try to put that into some kind of financial perspective, holding $85 million in assets in 1865 is equivalent to nearly $23.8 billion today.[3]

Staggering.

In 2023, it boggles the mind, this repulsive assignment of a dollar value to human life. Some would have us forget this part of our collective history. So this is the moment when I circle back to the beginning of this story and tell you what I left out two years ago.

10 November 1874

A Justice of the Peace in Richmond, the Fort Bend county seat, met with a husband and wife. Their purpose: to record a list of the 23 people who had once been their “property” and were set free some nine years earlier.[4]

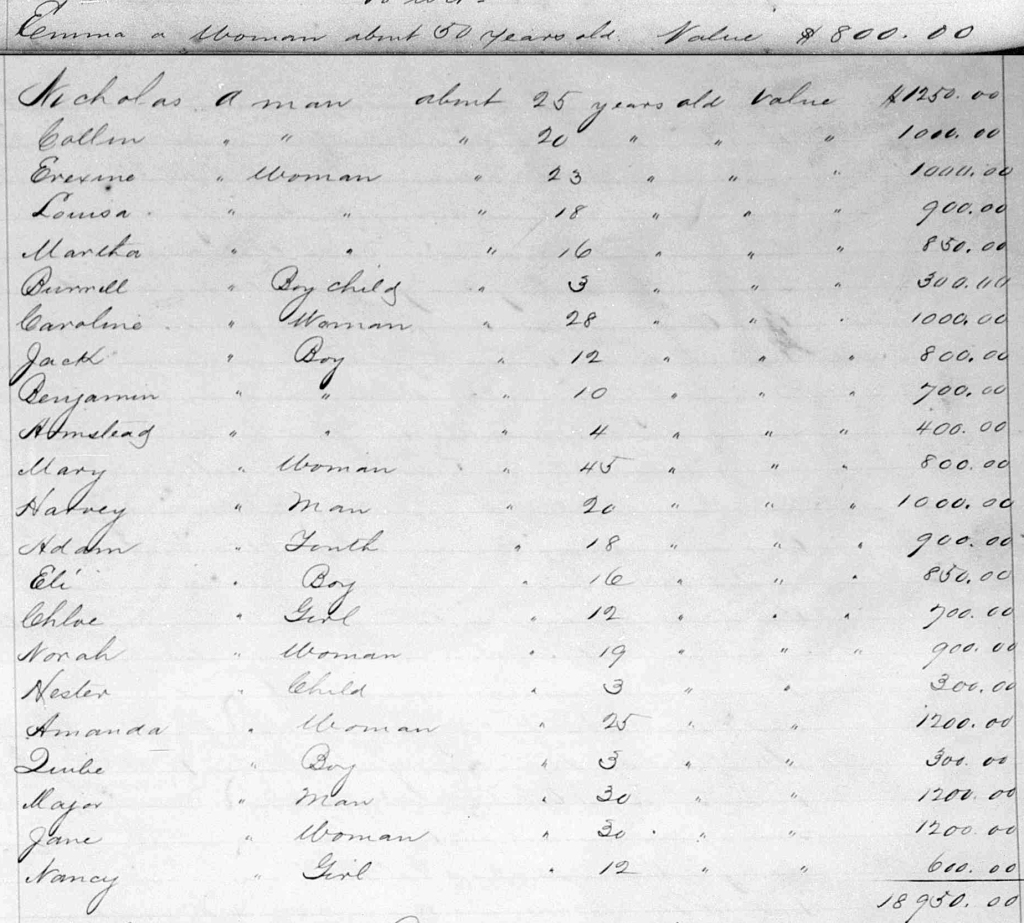

This was what the list actually looked like, with their names, approximate ages, and values. (Full disclosure: Emma’s name appeared on the bottom of one page and the rest were on a second page. For simplicity and unity, I have combined those images here.)

The reason the couple chose to record this in 1874 is not stated. Perhaps the tally at the bottom of the list has something to do with it: $18,950, which calculates to nearly $5.3 million in 2023 dollars.[5]

I did not notice a flurry of similar recordings by other former enslavers, but to be honest I didn’t keep looking. I’ll save the conjecture for another time since I have not thoroughly researched the possibilities. (Perhaps knowlegeable readers can shed some light.)

On the one hand, this filing did not surprise me. Genealogists and historians understand financial records sometimes are the only records available for finding names of African-American forbears prior to the 1870 census.

On the other, this was not a will bequeathing human beings to heirs. This was not a bill of sale. This was an inventory—an inventory recorded more than nine YEARS after Gen. Granger’s General Order No. 3. Nine YEARS after the persons named gained their freedom!

I felt profoundly moved by this list. I saw mothers and fathers. Daughters and sons. Brothers and sisters. Perhaps even a grandmother or two.

And I wanted to do something about it…

Subscribe/follow to be notified when the next installment is published.

#juneteenth #emancipated #africanamericangenealogy

[1] “Texas Reconstruction to the 20th Century, Part 1,” Texas Almanac, https://www.texasalmanac.com/articles/texas-reconstruction-to-the-20th-century, accessed July 2023.

[2] “TEXAS IN A NUTSHELL,” Daily News (Denison, Texas), Vol. 2, No. 211, Ed. 1, 27 October 1874, p. 1; The Portal to Texas History https://texashistory.unt.edu, accessed July 2023.

[3] MeasuringWorth, https://www.measuringworth.com/dollarvaluetoday/result.php?year=1865&amount=85,000,000&transaction_type=WEALTH, accessed July 2023.

[4] Fort Bend County, Deed Records, deed book K, 1837-1878, p. 256-257, Family History Library microfilm 007903249, viewed digitally, https://familysearch.org, accessed October 2022.

[5]MeasuringWorth, https://https://www.measuringworth.com/dollarvaluetoday/result.php?year=1865&amount=18950&transaction_type=WEALTH, accessed July 2023.

Unsettling, for sure. Were they applying for some sort of restitution for their “stolen property”?

LikeLike

I’m not sure. It is curious.

LikeLike